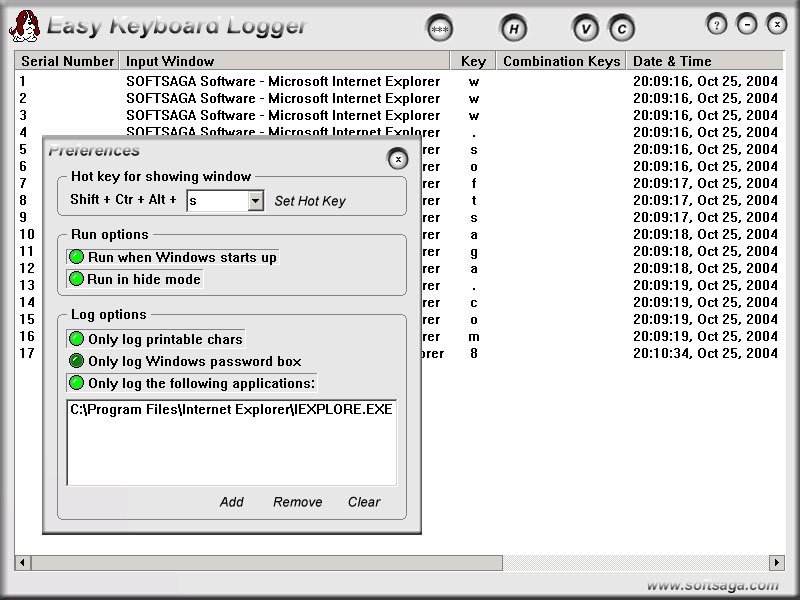

Working in Sweden prior to and during World War II, Torbjörn Caspersson and his student Bo Thorell observed that rapidly dividing undifferentiated cells, including embryonic cells and blood progenitors, have increased levels of RNA relative to mature cells ( Caspersson and Schultz, 1939 Thorell, 1947) ( Fig. In addition, by the 1940’s, it was already known that the levels of RNA can vary widely in different cell types. It took until the 1960’s for these structures, called lampbrush chromosomes, to be shown as corresponding to sites of high levels of transcription ( Callan, 1987 Flemming, 1882). The pioneering German biologist Walther Flemming, who studied the behavior of chromosomes at mitosis and coined the term “chromatin”, described in 1882 a very peculiar structure of the chromosomes in growing amphibian oocytes ( Fig. As documented in the examples reviewed below, hypertranscription may be essential to fuel the biosynthetic demands of rapidly growing stem and progenitor cells during development.Įvidence suggestive of hypertranscription has been present for many decades. While the regulation of RNA stability can contribute to changes in steady-state levels of transcripts, for clarity we propose that the term hypertranscription be used to refer to cases where there is a global elevation in nascent transcription. The goal of this review is to prompt researchers to consider analyzing hypertranscription in their developmental contexts of interest, and the accumulation of further studies may in the future help refine the definition of hypertranscription. Hypertranscription is therefore defined here in a relative and not an absolute sense. This increase in nascent transcriptional output may be relative to an earlier or subsequent developmental stage, or to neighboring cells, and is often associated with an increase in cell proliferation ( Guzman-Ayala et al., 2015 Koh et al., 2015 Nie et al., 2012). A concomitant increase in the synthesis of ribosomal RNA, the major RNA fraction in the cell, is also a component of hypertranscription. Hypertranscription can be defined as the coordinate increase in the nascent output of the majority of the transcriptome, including “housekeeping” genes such as those coding for ribosomal proteins ( Guzman-Ayala et al., 2015 Mattout and Meshorer, 2010). This state is associated with a particularly open, permissive chromatin structure ( Efroni et al., 2008 Gaspar-Maia et al., 2011 Meshorer et al., 2006). Moreover, recent studies indicate that stem cells can exist in a state of hypertranscription, which may also be called hyper-active transcription ( Efroni et al., 2008) or transcriptional amplification ( Lin et al., 2012 Nie et al., 2012). For example, energy metabolism can vary greatly in stem cells depending on their state or age ( Ito and Suda, 2014 Mohrin et al., 2015 Zhou et al., 2012). There can be major differences in functions that are often considered as “housekeeping” between stem cells and their differentiated progeny, or even between different states of the same stem cell type.

While this allows for the identification of highly tissue- or state-specific developmental regulators, it can provide an incomplete picture of the ways in which the transcriptomes of distinct cell types differ.

When comparing different cell types or states, researchers tend to focus on identifying the most differentially expressed genes, with the general assumption that the rest of the transcriptome is largely unchanging, or “housekeeping”. Understanding the composition and dynamic nature of the transcriptome is therefore of fundamental importance in stem cell and developmental biology. Developmental progression involves widespread changes in gene expression, and biologists routinely use the transcriptional profile to define a particular cell state. Here we discuss our mechanistic understanding of hypertranscription-induced replication stress and the resulting cellular responses, in the context of oncogenes and targeted cancer therapies.Gene expression triggers the emergence of phenotype from genotype during embryonic development and stem cell differentiation. A growing number of recent studies are reporting that oncogenes, such as RAS, and targeted cancer treatments, such as bromodomain and extraterminal motif (BET) bromodomain inhibitors, increase global transcription, leading to R-loop accumulation, transcription–replication conflicts, and the activation of replication stress responses. Despite the widely accepted importance of oncogene-induced hypertranscription, its study remains neglected compared with other causes of replication stress and genomic instability in cancer. Oncogenic signaling can promote global increases in transcription activity, also termed hypertranscription. Replication stress results from obstacles to replication fork progression, including ongoing transcription, which can cause transcription–replication conflicts.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)